Here is a summary of a

new working paper that I just published with

Anders Gustafsson.

We start by citing Francic Fukuyama:

I concur with the commonplace judgment that the rise of populism has been triggered by globalization and the consequent massive increase in inequality in many rich countries

We believe that Fukuyama is right in his description of the "commonplace judgment", and there are some papers that seemingly support that view, such as the

Importing Political Polarization paper by Autor et al. These papers typically identify clear causal effects, such as rising trade with China leading to lower employment in US manufacturing and that districts exposed to larger increases in import penetration elected politically more extreme political candidates.

It is, however,

a big step to jump from these partial effects to the conclusion that populism has been triggered by globalization. Trade with China may have had more beneficial consequences elsewhere in the US economy, and economic globalization is more than just trade with China. Similar points have also

been made by

Paul Krugman in a comment on the Autor papers.

One might also worry that papers that identify interesting effects of economc globalization are more likely to be published, while papers with imprecicely estimated zero-effects might not even be completed and/or submitted.

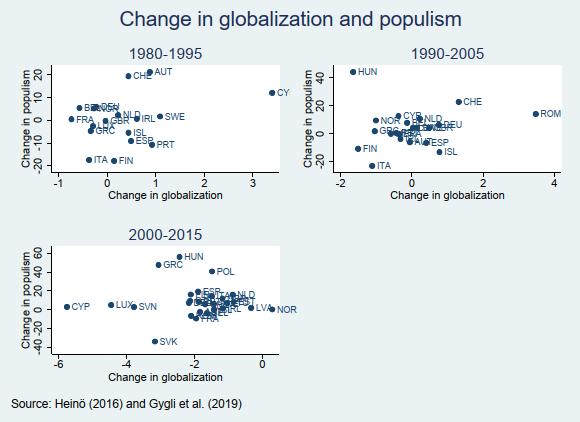

Our working paper checks if there is a pattern across countries such that populist parties have grown more in countries where globalization has increased more.

We do so using the KOF globalization index and the

compilation of election results for populist parties in Europe produced by Swedish thinktank Timbro. The compilation covers 33 European countries (included when they become politically free) during the period 1980-2018).

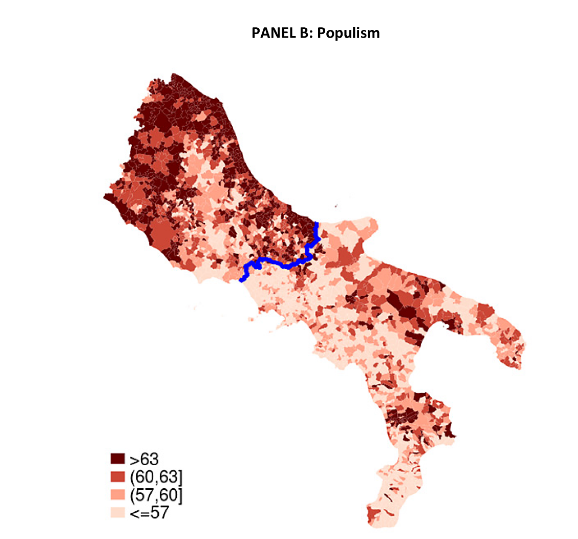

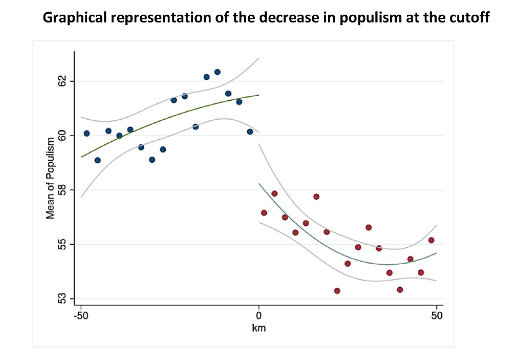

As it turns out, the commonplace judgement alluded to by Fukuyama is not visible to the eye when comparing increases in populist parties' voteshares and increases in globalization over different time periods:

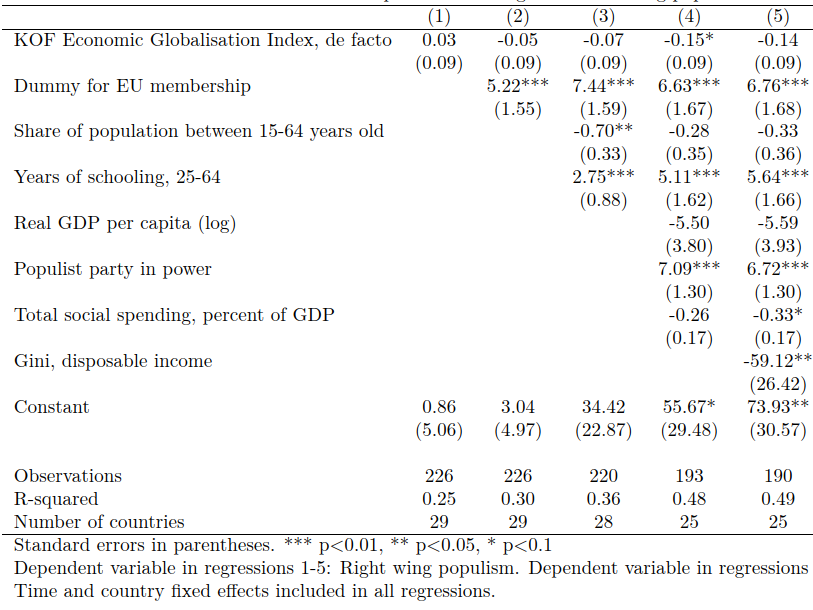

A nice feature of Timbro's compilation is the separation of populist parties into right-wing and left-wing populism. Dividing data into 4-year intervals and running regressions using KOF:s measure of economic globalization de facto (that combines trade in goods, services and trade partner diversity with financial globalization) and right-wing populist vote shares with country and time fixed effects reveals no significant correlation between the two. does in fact reveal a significant positive correlation between the two. The reason is, however, that EU-countries have more economic globalization and also more right-wing populism. Once EU-membership is controlled for, there is no positive association between economic globalization and right-wing populism.

Here is what the fixed effect panel regression with right-wing populist voteshares as dependent variable looks like:

[EDIT March 2020: Oops, time-FE was not included in column 1 - fixed now]

In the working paper, we show results also for left-wing populist parties (typically smaller in more globalized countries), random effects instead of country fixed effects (almost identical results) and other types of globalization. The main result is always that once EU-membership is controlled for, more globalized countries if anything have slightly smaller populist parties.

Note also that income inequality (measured using the Gini-coefficient for disposable income

taken from Swiid) is typically negatively associated with populism.

Needless to say, these are only correlation. But even if Fukuyama is right that income inequality somehow causes populism, it seems that countries with more inequality for other reasons still end up with less populism on average.

Finally, the fact that EU-membership is associated with about 7 percentage points bigger right-wing populist parties is pretty interesting. It suggests that the European Union does not fully succeed in promoting its

official goals (among which we find tolerance, inclusion, justice, non-discrimination as well as social and territorial cohesion and solidarity). The EU-effect is very much in line with a pattern

recently noted by

Dani Rodrik, that right-wing populists in Europe portray the EU and the elites in Brussels as their enemy, not free trade.