New paper on how the benefits of economic freedom are distributed

A long time ago, I wanted to examine how (or if) increases in economic freedom correlate with changes in income inequality. As I immediately found out, my friend and colleague Niclas Berggren had already attacked the question in Public Choice back in 1999, although with mixed results based on the limited data that were available at the time.

Together with Therese Nilsson, I published some more robust patterns in European Journal of Political Economy in 2010:

Using the Standardized World Income Inequality Database, we examine if the KOF Index of Globalization and the Economic Freedom Index of the Fraser institute are related to within-country income inequality using panel data covering around 80 countries 1970–2005. Freedom to trade internationally is robustly related to inequality, [...] Reforms towards economic freedom seem to increase inequality mainly in rich countries, and social globalization is more important in less developed countries. Monetary reforms, legal reforms and political globalization do not increase inequality.

Still, the field as a whole was full of conflicting findings, as demonstrated for example by Bennet & Nikolaev in 2016:

we replicate the results from two significant studies using six alternative measures of income inequality for an updated dataset of up to 112 countries over the period 1970–2010. Notably, we use the latest release of the Standardized World Income Inequality Dataset, which allows us to account for the uncertainty of the estimated Gini coefficients. We find that the results of previous studies are sensitive to the choice of country sample, time period and/or inequality measure used.

A couple of years ago - in Ohio of all places - Christian Bjørnskov fiddled around with a new data source: The global consumption and income project, and we started a paper that just came out in Kyklos:

Bergh, Andreas, and Christian Bjørnskov. 2021. "Does Economic Freedom Boost Growth for Everyone?" Kyklos 74(2): 170–86. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/kykl.12262 (April 13, 2021).

The paper essentially does three things

- We summarize research on specific reforms that increase economic freedom and causally affect income or productivity

- We note that these reforms have ambiguous implications for inequality as measured by the Gini-coefficient, because they could benefit high-income earners by increasing the returns to capital (at least in the short to medium run), and simultaneously benefit low-income earners by lowering barriers to entry and promoting competition more generally.

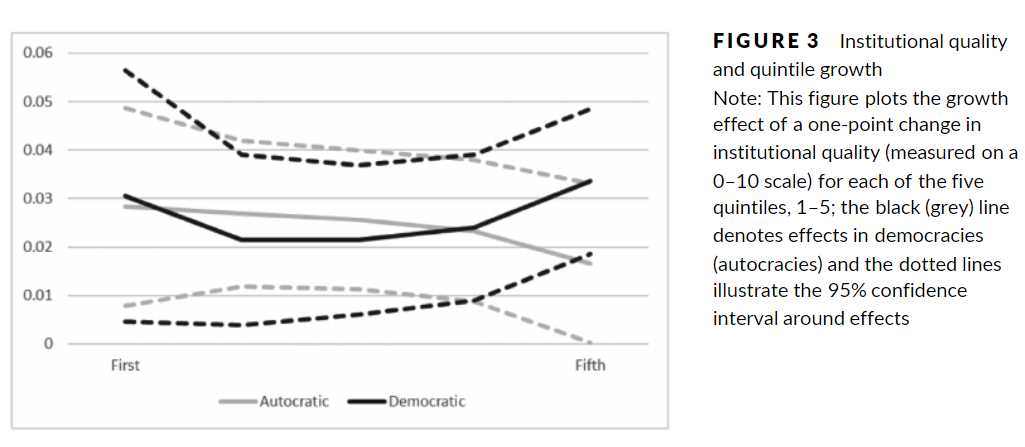

- We estimate the association between economic freeom and income growth for each quintile of the income distribution, and show that economic freedom affects seems to affect all parts of the income distribution roughly equally. However, in democracies, the point estimate is indeed larger for the lowest and the highest quintile:

Potentially, this explains the mixed findings in studies using the Gini-coefficient.

From the paper:

To illustrate the size of our estimated associations, we note first that (as shown in Table 1) incomes grow on average between 8% and 9% over a five-year period in our sample. Based on the estimates in democracies, a one standard-deviation increase in institutional quality is associated with roughly 6 percentage units of higher income growth in quintiles one and five, and roughly 4 percentage units of higher growth in quintiles two, three, and four. While these differences are in line with the idea that economic freedom reforms benefit mainly the top and bottom of the income distribution, the differences between quintiles are far from statistically significant