Andreas Bergh, Associate professor at Lund university

and the Research Institute of Industrial Economics

Google scholar (Aug 2024)

Current research (selection):

Can trust surveys be trusted?

Urban rural polarization

Populism and inequality

Formal vs informal institutions

Tweeting municipalities

Publications

2023

Bergh, A. & Erlingsson, G. 2023. Municipally owned corporations in Sweden: A cautionary tale.

Public Money & Management (forthcoming).

Link.

2022

Bergh, A. & Kärnä, A. 2022. Explaining the rise of populism in European democracies 1980-2018: The role of labor market institutions and inequality.

Social Science Quarterly 103(7): 1719-1731.

Länk.

Bergh, A. & Wichardt, P. 2022. Mine or Ours? Unintended framing effects in dictator games.

Rationality & Society 34(1): 78-95.

Link.

2021

Bergh, A. & Bjørnskov, C. 2021. Does economic freedom boost growth for everyone? Kyklos 74: 170-186. Link.

Bergh, A. & Bjørnskov, C. 2021. Trust Us to Repay: Social trust, long-term interest rates, and sovereign credit ratings. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 53(5). Link.

Bergh, A., Erlingsson, G. & Wittberg, E. 2021. What happens when municipalities run corporations? Empirical evidence from 290 Swedish municipalities. Local Government Studies 48(4): 704-727.

Bergh, A., Funcke, A. & Wernberg, J. 2021. The sharing economy: Definition, measurement and its relationship to capitalism. International Review of Entrepreneurship 19(1).

Bergh, A. 2021. The compensation hypothesis revisited and reversed.

Scandinavian Political Studies 44(2): 140-147.

Link.

Bergh, A. & Kärnä, A. 2021. Globalization and populism in Europe.

Public Choice 189: 51–70.

Link.

2020

Bergh, A. & Bjørnskov, C. 2020. Does big government hurt growth less in high-trust countries?

Contemporary Economic Policy 38(4): 643-658.

Link.

Bergh, A., Nilsson, T. & Mirkina, I. 2020. Can social spending cushion the inequality effect of globalization?

Economics & Politics 32(1): 104-142.

LInk.

2019

Bergh, A. & Funcke, A. 2019. Social trust and sharing economy size: Country-level evidence from home sharing services.

Applied Economics Letters 27(19): 1592-1595.

Link.

Berggren, N., Bergh, A., Bjørnskov, C. & Tanaka, S. 2019. Migrants and life satisfaction: The role of the country of origin and the country of residence.

Kyklos 73(3): 436-463.

Link.

Bergh, A. 2019. Hayekian welfare states: Explaining the co-existence of economic freedom and big government.

Journal of Institutional Economics 16(1): 1-12.

Link.

Lead article!

2018

Bergh, A., Erlingsson, G., Gustafsson, A. & Wittberg, E. 2018. Municipally owned enterprises as danger zones for corruption? How politicians having feet in two camps may undermine conditions for accountability. Public Integrity 21(3): 320-352.

Bergh, A. & Öhrvall, R. 2018. A sticky trait: Social trust among Swedish expatriates in countries with varying institutional quality.

Journal of Comparative Economics 46(4): 1146-1157.

Link.

Bergh, A. & Wichardt, P. 2018. Accounting for context: Separating monetary and (uncertain) social incentives.

Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 72: 61–66.

Link.

2017

Bergh, A., Fink, G. & Öhrvall, R. 2017. More politicians, more corruption: Evidence from Swedish municipalities.

Public Choice 172(3–4): 483–500.

Link.

Bergh, A. 2017. Explaining cross-country differences in labor market gaps between immigrants and natives in the OECD.

Migration Letters 14(2): 243–254.

Link.

Bergh, A., Dackehag, M. & Rode, M. 2017. Are OECD policy recommendations for public sector reform biased against welfare states? Evidence from a new database.

European Journal of Political Economy 48: 3–15.

Link.

2016

Nothing

2015

Bergh, A. 2015. The future of welfare services: How worried should we be about Baumol, Wagner and aging?

Nordic Economic Policy Review 2-2015.

Link.

Bergh, A., Nilsson, T. & Mirkina, I. 2015. Do the poor benefit from globalization regardless of institutional quality? Applied Economics Letters 23(10): 708-712.

Bergh, A. & Henrekson, M. 2015. Government size and growth: A rejoinder.

Journal of Economic Surveys 30(2): 393–396.

Link.

Berggren, N., Bergh, A. & Bjørnskov, C. 2015. What matters for growth in Europe? Institutions versus policies, quality versus instability. Journal of Economic Policy Reform 18(1).

Bergh, A. 2015. Yes, there are Hayekian welfare states (at least in theory). Econ Journal Watch 12(1): 22-27.

2014

Bergh, A. & Bjørnskov, C. 2014. Trust, welfare states and income equality: Sorting out the causality. European Journal of Political Economy 35: 183-199.

Bergh, A. & Nilsson, T. 2014. Is globalization reducing absolute poverty? World Development 62: 42–61.

Bergh, A. & Nilsson, T. 2014. When more poor means less poverty: On income inequality and purchasing power. Southern Economic Journal 81(1): 232-246.

Bergh, A., Nilsson, T. & Mirkina, I. 2014. Globalization and institutional quality: A panel data analysis. Oxford Development Studies 42(3): 365-394.

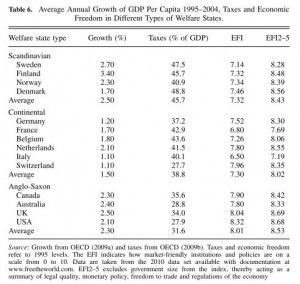

Bergh, A. 2014. What are the policy lessons from Sweden? On the rise, fall and revival of a capitalist welfare state. New Political Economy 19(5): 662-694.

2013

Bergh, A. & Lyttkens, C. H. 2013. Measuring institutional quality in ancient Athens. Journal of Institutional Economics 9(2): 235-258.

2012

Berggren, N., Bergh, A. & Bjørnskov, C. 2012. The growth effects of institutional instability. Journal of Institutional Economics 8(2): 187-224.

2011

Bergh, A. & Henrekson, M. 2011. Government size and growth: A survey and interpretation of the evidence. Journal of Economic Surveys 25(5): 872-897.

Bergh, A. & Bjørnskov, C. 2011. Historical trust levels predict current welfare state size. Kyklos 64(1): 1-19. Lead article.

2010

Bergh, A. & Nilsson, T. 2010. Do liberalization and globalization increase income inequality? European Journal of Political Economy 26(4): 488-505.

Bergh, A. & Nilsson, T. 2010. Good for living? On the relation between globalization and life expectancy. World Development 38(9): 1191-1203. Lead article.

Bergh, A. & Karlson, M. 2010. Government size and growth: Accounting for economic freedom and globalization. Public Choice 142(1): 195-213.

2009

Bergh, A. & Fink, G. 2009. Higher education, elite institutions and inequality. European Economic Review 53: 376-384.

Bergh, A. & Erlingsson, G. 2009. Liberalization without retrenchment: Understanding the consensus on Swedish welfare state reforms. Scandinavian Political Studies 32: 71-94.

2008

Erlingsson, G. O., Bergh, A. & Sjölin, M. 2008. Public corruption in Swedish municipalities: Trouble looming on the horizon? Local Government Studies 34: 595-608.

Bergh, A. 2008. A critical note on the theory of inequity aversion. Journal of Socio-Economics 37: 1789-1791.

Bergh, A. & Fink, G. 2008. Higher education policy, enrollment, and income inequality. Social Science Quarterly 89(1): 217-235.

Bergh, A. 2008. Explaining the survival of the Swedish welfare state: Maintaining political support through incremental change. Financial Theory and Practice 32(2): 233-254.

2007

Bergh, A. 2007. The middle class and the Swedish welfare state: How not to measure redistribution. The Independent Review 11(4): 533-546.

2006

Bergh, A. 2006. Work incentives and employment are the wrong explanation of Sweden’s success. Econ Journal Watch 3(3): 452-460.

Bergh, A. 2006. Is the Swedish welfare state a free lunch? A comment on Peter H. Lindert's book Growing Public. Econ Journal Watch 3(2): 210-235.

2005

Bergh, A. 2005. On inter- and intra-individual redistribution of the welfare state. Social Science Quarterly 86(5): 984-995.

Bergh, A. 2005. On the counterfactual problem of welfare state research: How can we measure redistribution? European Sociological Review 21(4): 345-357.

2004

Bergh, A. 2004. The universal welfare state: Theory and the case of Sweden. Political Studies 52(4): 745-766.

Bergh, A. 2004. On the redistributive effect of upper benefit limits in Bismarckian social insurance. Finnish Economic Papers 17(2): 73-78.

BOOKS AND BOOK CHAPTERS (selection)

Bergh, A. and Kärnä, A. 2024. Economic freedom and populism. In: Handbook of Research on Economic Freedom (ed. N. Berggren). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. Forthcoming.

Bergh, A. 2022. An All Too Successful Reform? The 1997 Overhaul of the Swedish Budget Process. Chapter 11 in "Successful Public Policy: Lessons From the Nordic Countries", edited by de La Porte, C., Kauko, J., Nohrstedt, D., ‘t Hart, P., & Tranøy, B. S. Oxford University Press.

Bergh, A., Bjornskov, C., and Vallier, K. 2021. "Social and Legal Trust: The Case of Africa" in Vallier and Weber (ed.) "Social Trust", New York: Routledge.

Link to book.

Bergh, A. 2021. "Poverty and New Welfare Economics." Ch. 8 in "Economists and Poverty", Lundahl, Rauhut & Hatti (ed.) Routledge.

Link to book.

Bergh, A. 2021. Incitament: Principaler, agenter och medarbetare. Kap. 11 i Bringselius (red.) Tillit och Omdöme. Studentlitteratur.

Bergh, A. 2019. Is Migration Threatening Social Trust in Europe? In: Trust in the European Union in Challenging Times, A. B. Engelbrekt, N. Bremberg, A. Michalski, L. Oxelheim (Eds), Springer.

Link.

Bergh, A., G. Erlingsson, M. Sjölin & R. Öhrvall 2016. A Clean House? Studies of Corruption in Sweden. Nordic Academic Press.

Link.

Bergh, A., T. Nilsson & D. Waldenström 2016. Sick of Inequality? Edward Elgar.

Link.

Bergh, A. 2015. "Comments on 'Collective Risk Sharing: The Social Safety Net and Employment' by Torben M. Andersen." Pp. 46-49 in Reform Capacity and Macroeconomic Performance in the Nordic Countries, edited by T. M. Andersen, M. Bergman and S. E. H. Jensen. Oxford, UK.: Oxford University Press.

Link.

Bergh, A. 2015. Den Kapitalistiska Välfärdsstaten. Studentlitteratur. (4th ed)

Nilsson, T. and A. Bergh. 2013. Income inequality, health and development – In search of a pattern. Pp. 441-468 in Research on Economic Inequality, volume 21: Health and Inequality, edited by Pedro Rosa Dias and Owen O’Donnell.

Bergh, A. och Henrekson, M. 2011. Government size and growth. American Enterprise Institute.

Bergh, A. 2010. Towards a New Swedish Model? in Bengtsson (ed)

Population Ageing - A Threat to the Welfare State?, Springer.

Link to complete book.

Bergh, A. and R. Höijer (editors). 2008.

Institutional competition. Edward Elgar.

Link.

Bergh, A. 2005. "Poverty and New Welfare Economics." In

Economists and Poverty, Rauhut, Hatti & Olsson (red.), Vedam eBooks (P) Ltd. 2005.

Link.

Bergh, A. 2003. Distributive Justice and the Welfare State. Lund Economic Studies 115, Dept. of Economics, Lund University.

BOOK REVIEWS (selection)

Bergh, A. 2012. Beyond Welfare State Models – Transnational Historical Perspectives on Social Policy – Edited by Pauli Kettunen and Klaus Petersen. In International Journal of Social Welfare, Volume 21, Issue 3, pages 319–320, July 2012.

Bergh, A. 2011. Nordics in Global Crisis: Vulnerability and Resilience by Thorvaldur Gylfason, Bengt Holmström, Sixten Korkman, Hans Tson Söderström, and Vesa Vihriälä. Journal of Economic Literature, March 2011.

Bergh, A. 2009. Full employment in Europe: Managing labour market transitions and risks - By Günther Schmid. Papers in Regional Science 88:883-885.

Outreach (selection)

Member of the editorial board of Riksbankens Jublieumsfond's yearbook.

PARTICIPATION IN RESEARCH PROJECTS AND ORGANIZATION OF CONFERENCES (selection)

‘Trust and corruption in swedish municipalities’ financed by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet).

Together with Niclas Berggren I have organized the international conference "Trust, Reciprocity and Social Capital" for young social scientists held in Stockholm August 25-26, 2006.

During 2004 and 2005, I was part of the research project "Ojämlikhet, omfördelning och socialförsäkringar" financed by The National Social Insurance Board, led by Fredrik Andersson at Dept of economics, Lund University.

INTERNATIONAL CONTACTS

2013 Research visit CesIfo institute, Munich.

2007 - 2017 Several invited research visits, Harvard School of Public Health

2004 Visiting Scholar at the Centre for Basic Research in the Social Sciences (presently the Institute for Quantative Social Science), Harvard University.

REFEREE WORK

Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Social Science Quarterly, European Journal of Political Economy, European Sociological Review, Public Choice, Social Policy & Administration

TEACHING EXPERIENCE AND COURSE EVALUATIONS

Microeconomics (first year course), Public Economics (second year course) and Institutional Economics (second year course) taught with very good student evaluations.

Guest lecturer for Uppsala Univerity, Försäkringskassan, Executive Foundation Lund (including the Executeve MBA-program), LTH (Fastighetsvetenskap)

PEDAGOGICAL TRAINING

Högskolepedagogik 10 credits, 2003.

Pedagogical training for supervising PhD-students, 2013

COURSE DEVELOPMENT

Development of material for the first year course in microeconomics: Exams, groupwork, internet-based questions, power points.

Development of an entirely new course in Institutional Economics

PUBLIC LECTURES

Regularly participates in public lectures, debates et cetera. Examples include lectures or debates at KPMG consulting, Försäkringskassan, Folkpartiet, Socialdemokratiska studentförbundet, Liberala ungdomsförbundet, Centerns ungdomsförbund, and various student organizations.