Torben M. Andersen has

a new book (co-edited with

Michael Bergman and

Svend E. Hougaard Jensen), and an

official government report (SOU 2015:53, bilaga 4 till Långtidsutredningen 2015) on the welfare state and economic performance. A particularly interesting idea is that Norway, Switzerland and the US are on the best-practice frontier in the efficiency equity space, suggesting that there is indeed some kind of Okun trade-off (

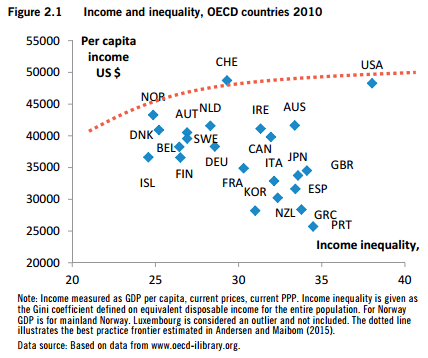

pdf), but also suggesting that it is not very steep.

Referring to figure 2.1 above, Andersen writes in the government report:

The analysis shows that

i) the elasticity of the frontier is close to minus one, i.e. a one percent lower equality is associated with a one percent higher income level,

ii) the slope of the frontier has not become more steep over the sample period (1980–2010), [...] and

iii) for the countries at or close to the frontier (best practice countries), there is a significant negative effect of taxes on both income and inequality, as predicted by standard theory.

The idea that a line connecting Norway, Switzerland and the US can be thought of as an efficiency frontier is interesting, but (in my view) misleading. By not accounting for the role of social trust, the trade-off seems less steep than it most likely is.

We know that countries with higher social trust tend to have higher economic growth (Algan and Cahuc, 2010; Dincer and Uslaner, 2010). A link has also been established from social trust to welfare state size (Bergh and Bjørnskov, 2011; Bjørnskov and Svendsen, 2012). Most importantly, social trust seems to cause equality both via the welfare state and directly (ie. when controlling for welfare state spending) (Bergh and Bjørnskov 2014).

The upshot of these findings (not cited by Andersen) - is that the countries on the frontier are improper counterfactuals for each other. A comparison between any Nordic country and the US is a comparison of a high-trust country to a medium-trust country. As a result, the efficiency-equity trade-off will appear relatively flat.

In reality, however, we simply do not know how USA would perform with tax revenue around 50 percent of GDP, as was the case for Sweden in the 1980s and still is the case in Denmark. Similarly, we do not know how a country with Nordic trust levels would perform with a public sector of US-size. Inference regarding the efficiency-equity trade-off should be based on cross-country evidence that control for trust. As a simple alternative we could draw the frontier between the US and a country with similar trust levels and higher equality, such as Austria or Germany (all with trust around 40 percent).

In any case: If we accept that Figure 2.1 can be thought of as a best practice frontier, the most striking pattern is arguably that most countries exhibit strikingly high levels of inefficiency.

---

Algan, Y., and Cahuc, P. (2010). Inherited Trust and Growth. American Economic Review, 2060-2092.

Bergh, A., and Bjørnskov, C. (2011). Historical trust levels predict the current size of the welfare state. Kyklos, 64, 1-19.

Bergh, A. and Bjørnskov, C. (2014). Trust, welfare states and income equality: Sorting out the causality. European Journal of Political Economy 35:183-199.

Bjørnskov, C., and Svendsen, G. (2012). Does social trust determine the size of the welfare state? Evidence using historical identification. Public Choice, 1-18.

Dincer, O.C., and Uslaner, E.M. (2010). Trust and growth. Public Choice, 142, 59-67.